Dave Waters

Geoscience Consultant - Fault Seal Analyst at a London Client

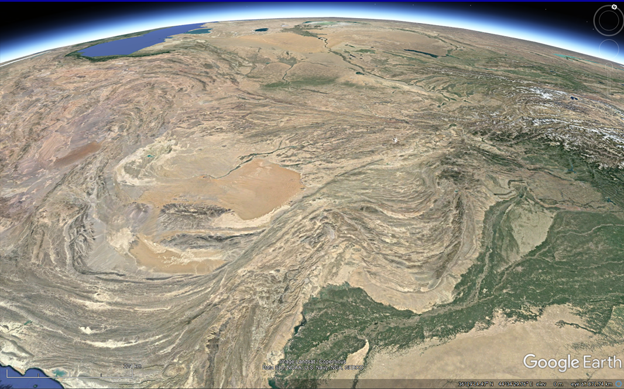

Few people could argue with the assertion that the Himalaya and Tibet represent the “roof of the world”. Anybody who has ever meditated on plate reconstructions, will recognise the startling “momentum” with which the Indian subcontinent has slammed determinedly, in a Formula-1 of continents - into Asia’s underbelly – having ramifications throughout the supercontinent. Everest, K2 and their siblings stand as sentinels to a swathe of forces that we can barely comprehend. In flights from Tokyo to London I’ve looked down on the towering mountain fronts that still permeate even Siberia far to the north, in awe at a collision that continues today. Rocks made more fluid and mobile by deep driven realms more titanic than we can ever truly appreciate.

Yet if the Himalaya are the roof of the world, then the Tien Shan and the Hindu Kush are separated only in trend and geographic location. They are part of that same roof and the same drama. Three countries that inhabit them, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, have long transfixed me. Few large countries in the world, excepting maybe Bhutan and Nepal, can claim to be so totally dominated by high (and we are a talking really high) mountains.

Afghanistan- mountains in motion in more ways than one: Picture Credit: c/o Google Earth

The drama in these countries has not just been a geological one. Today, I choose from these three to focus on Afghanistan. The human and historical drama there, though it can’t compete with the geology for duration, has been as jagged and sharp as any mountain peak.

I first recall it entering my own awareness with the Soviet “intervention” that initiated in 1979. Since then the tussles for power have been virtually constant. In a visit to Tehran near the turn of the millennium, the effect this has had on the whole region, particularly neighbouring Iran and Pakistan, was very evident. For all the criticism levelled at Iran they have long harboured millions of Afghan refugees in ways, for all the undeniable issues arising, that put western country refugee responses in the dark ages by comparison. Indeed, despite all the bad press of the 9-11 years, the resourcefulness and humility of the Afghan diaspora is something most of us have likely encountered, whether we realise it or not. The number of Afghan professors, doctors, lawyers, driving taxis around many of the world’s megacities would surprise us, and humble us.

Amidst all the current distractions, it may or may not have escaped our attention that the US has also now entered a phase of departure from Afghanistan. I am not going to comment on that, it’s not my interest here, save to say that it does herald a new and uncertain era. The ongoing power plays between rival forces, including those invested in the world’s largest opium producing region, will not go away soon. Neither will recriminations for past injustices. For all that, prosperity is a great moderator, and battle fatigue eventually sets in for even the hardiest of warriors. There is a side to Afghanistan that we are less familiar with, that is endowed with opportunity and a longing for a patiently awaited prosperity.

The resilience of the people, now numbering 35 million within Afghanistan, and perhaps another 4-5 million around the world, mainly in Pakistan and Iran, is of course the greatest resource. As many of us around the world grapple with unfamiliar hardships and constraints on supply – these are barely a dent compared to what much of the Afghan population has endured for decades.

Whatever our view of Uncle Sam, there is no doubt that wherever he arrives, he throws a few resources around. One result of that is a lot of effort has occurred over the past few years in better understanding and documenting Afghanistan’s resources – of all kinds. As the country embarks on a new phase, that is something all its indigenous players can utilise to advantage (whether uncle likes it or not). Watch too - as the indigenous situation becomes less dominated by superpowers, Russian or US - for more interest in investment from neighbouring Asian countries.

Mountain belts of Eurasia are a particular love of mine. Though I cannot claim to have ever visited Afghanistan – not yet – only its airspace - those of us who have walked or in other ways witnessed spines of Eurasia’s lofty ranges will understand the shear awe they can invoke. Not least because of the scale of the event they represent, reaching from Korea to Iberia, exhumed from the bowels of the ancient Tethyan Ocean that once lay north of India, Arabia and Africa, in both its palaeo- and neo- incarnations. These mountains, the same ones that block easy human passage so effectively, and make Afghanistan so strategic a human fortress, are the same ones that block weather patterns. That means snow, ice, and seasonal rain and melt. Of course, climate is under the microscope at the minute, but the Hindu-Kush and Tien Shan are the vanguard of a wall that will long disrupt any air-flows in the region.

Making the most of this seasonal water influx, though lean by many world standards, is the blessing that sustains the Afghan economy, amidst a dry region of the Eurasian supercontinent. It is assisted by the fact that much of it falls as winter snows in the highlands, prolonging the melt and the use. This means that the nuts and fruit produce of Afghanistan are prized amongst Asia. The almonds, walnuts, pomegranates, grapes, apples, apricots. They thrive. Dried fruit also, such as raisins – are a huge export.

Afghan gems meanwhile, are something to raise the eyebrows of even King Solomon. This is not an unusual feature of intermontane belts that represent past volcanic arcs of long-gone oceans. Lithium too, is a not unfamiliar presence in such geologies, as it also is in high, arid, montane, salar-dotted regions like the Andes. The country’s large active fault systems, although an earthquake threat, locally provide elevated heat flows with geothermal energy potential, to complement a big and largely untapped opportunity for micro-hydro and solar.

Though indigenous hydrocarbon resources are limited, they are not absent, where the mountain fronts of the country meet the Eurasian steppes in the foothills and forelands of the northern plains. Though the Sulaiman range (Salt range) hydrocarbon resources present in Pakistan will be more disrupted by faulting in Afghanistan, there is no lack of opportunity for “out of the box” thinking. Copper, Gold, Uranium, Iron, Tungsten, Lead, Zinc, Mercury, REE's are all documented, and await the day Afghanistan’s rival factions can work together. Mining technologies are advancing at a rate for the country to be able to exploit these in new, advanced, kinder to the environment ways.

Of tourism, it would be foolish to ignore that there can be risks to travellers in regions of ongoing conflict. When a country has been trodden on as thoroughly and persistently as Afghanistan has, a wariness to foreigners can be forgiven. Yet the history of much of Afghanistan is overwhelmingly one of hospitality to visitors, if they come with intentions that do not involve control. The most unstable areas are well documented, and the areas safer to travel to contain visual spectacles to match anything the gems can offer, not to mention the splendour of the carpet industry. The passion with which those who have visited the country frequently speak, and the passion with which diaspora return, is testimony to the grandeur. It is a niche tourist market perhaps, but one that if undertaken with care, and the invitation of locals, can flourish.

So, what is all this to us? Well Afghanistan will, I suspect, long be cautious towards outside intentions – especially those directed at its resources. Who can blame it? If, however, there is opportunity to share what we can discern and document - as Afghans begin a long, and no doubt obstacle-laden course of refreshing their economy, then why not?

The world of geoscience may be in various turmoils at the moment, but there is never, ever, any shortage of things to do. Afghanistan is difficult, let’s be clear - but lacking in opportunities it is not. We can do worse than help Afghans, of all dispositions, and countries like it, to find those opportunities. When things take a turn for the unexpected, the best thing for explorers to do, always, is to explore.

If you have news or commentary you would like to share, please contact us and we will be in touch.

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy