On the same day that Rachel Reeves was announcing her Autumn Budget, the National Energy System Operator, NESO, quietly issued a bombshell warning about the risks the UK might start running out of gas on cold winter days as a result of the possible closure of offshore pipeline infrastructure. National Gas has been warning about these risks for some time, saying privately they may manifest as early as next winter. NESO is more optimistic. I sit somewhere in between.

Britain’s gas pipelines are at risk

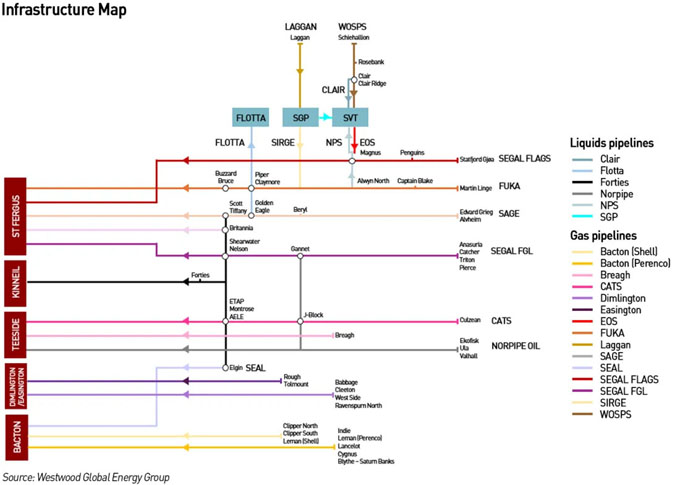

The gas system in GB today depends on four main supply routes into the National Transmission System (“NTS”):

- The UK Continental Shelf (“UKCS”): gas from North Sea and East Irish Sea fields enters the NTS via onshore terminals at St Fergus, Teesside, Bacton, Easington, and Barrow. UKCS production has fallen from around 100 bcm /year in 2000 to around 30 bcm more recently - roughly 35–40% of GB annual demand

- LNG imports: Milford Haven (South Hook, Dragon) and Isle of Grain can deliver a combined 130–150 mcm /day, equivalent to around half of GB’s theoretical peak-day demand, but only if tanks are full and send-out is not constrained by regas capacity, shipping delays or NTS constraints

- Norwegian pipelines: Langeled, Vesterled, and the Tampen Link bring Norwegian gas mainly to Easington and St Fergus. Combined they can supply roughly 80–100 mcm /day, though actual flows vary with continental nominations

- Interconnectors: the Bacton–Zeebrugge (“IUK”) and Bacton–Balgzand (“BBL”) pipelines connect GB to northwest Europe. In theory they allow imports of 60–70 mcm /day. They typically export gas to Europe in the summer and import in the winter (effectively using European gas storage facilities although there are no explicit contracts behind that)

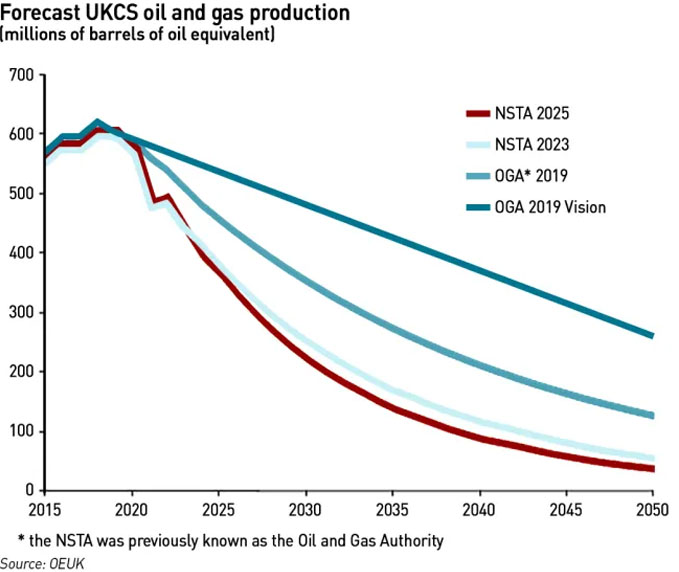

The North Sea Transition Authority’s (“NSTA’s”) latest projections show accelerating UKCS decline through the 2020s, and 2025 was the worst year for exploration on the UKCS since the basin began to be developed. According to Wood Mackenzie, no exploration wells were drilled in UK waters this year, the first time there has been no fresh exploration activity in the basin since oil and gas was found there in the 1960s.

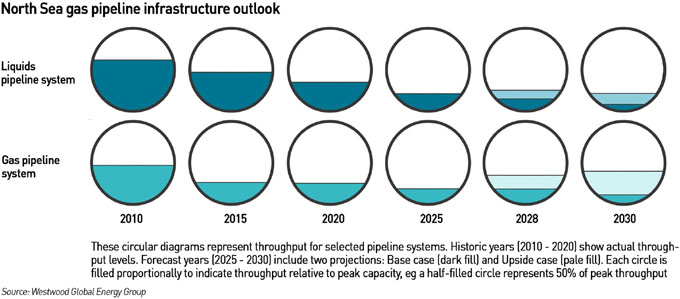

The UKCS is in a much sharper decline than had previously been expected, primarily as a result of a punitive fiscal regime and current Government policy against new exploration. This not only threatens energy security in terms of access to molecules, it also threatens the viability of offshore pipeline infrastructure. The key issue isn’t simply that UKCS output is declining, but that the offshore gathering and transmission system has fixed costs and physical interdependencies - as throughput falls, it becomes progressively harder to maintain and justify these assets.

These pipelines were designed for high throughput and depend on tariffs from producers for their economic viability. As volumes decline, unit tariffs rise to recover fixed costs. At some point, remaining producers face uncompetitive transportation tariffs which accelerates field decommissioning, leading to a “death spiral” where loss of one anchor field undermines the economics of the whole system.

According to Westwood Global Energy Group, the Reserves/Production (R/P) ratio, a measure of how long an asset could continue to produce at current rates, given remaining reserves and 2025 production estimates, for four pipeline systems is <6, two of these are critical for the UK with a high number of field entrants.

Flotta Pipeline System: relies on production throughput from three hubs (seven producing fields). Although infill drilling and workover activity is ongoing at the hubs, the R/P ratio is 5.5. The progression of the Marigold discovery as a tieback to the Piper hub would change the current outlook. Roughly 40% of the resource upside within 50 km is unlicensed.

Forties Pipeline System: a critical liquids pipeline system for the UK, with 71 field entrants via 17 hubs, accounting for around 23% of UK liquids throughput in 2025. Seven hubs, could cease before 2030, including the namesake Forties putting the system at risk. There is one tieback under development and infill drilling at some hubs, but due to the relatively high current throughput rates versus the reserves replacement the R/P ratio is 5.5. Three hubs are expected to contribute 45% of 2025 throughput. Delivery of upside opportunities, such as an infill well at Elgin, additional drilling at ETAP and progression of new developments such as Birgitta, Fotla and Leverett, would improve the outlook for this system. Over half of the resource upside within 50 km is unlicensed.

CATS Pipeline System: a critical gas pipeline system for the UK, with around 42 field entrants via nine hubs, contributing roughly 25% of UK gas throughput in 2025 but due to the relatively high current throughput rates compared with the reserves replacement, the R/P ratio is 5.0. Two hub entrants account for 68% of 2025 forecast throughput. Strong performance from a development well being drilled at Culzean (largest entrant), the progression of ongoing drilling opportunities at J-Block and ETAP, and development of tieback opportunities at Birgitta will be important to the outlook. There is high upside potential within proximity of the hub entrants.

Ninian Pipeline System: the most northerly pipeline system in the UK feeds liquids production from three hubs via 12 fields. The Ninian hub has commenced decommissioning activities, with only one of the three original platforms still operating. The pipeline, however, feeds into the Sullom Voe terminal which also receives oil from Clair and Clair Ridge and therefore supports economics. Over 80% of the resource upside within 50 km of the Ninian Pipeline System is unlicensed.

Liquids and gas export routes are intrinsically linked: changes to one export route can impact many other export routes. This interdependency means that if one system becomes uneconomic, it could lead to a cascading effect forcing the closure of other systems, stranding potentially viable fields and leaving some areas of the North Sea inaccessible for future development.

When an offshore trunkline is decommissioned, all connected satellites lose evacuation routes. For example, closure of the SAGE or FLAGS system would strand several smaller tiebacks. Once a trunk is gone, re-establishing offshore transport to shore would require new infrastructure which would be uneconomic for tail-end volumes. With each major offshore system that shuts down, the steady baseload flow into the NTS diminishes, which has several system-level implications:

- Reduced baseline inflow capacity: St Fergus, historically a high-pressure feed point, is already seeing declining flows. As these terminals wind down, the NTS loses one of its few north-to-south supply anchors, increasing reliance on southern entry points (Easington, Bacton, LNG). This complicates linepack management and reduces network flexibility under high demand

- Greater dependence on LNG: LNG can physically fill the gap on paper, but it is price sensitive as cargoes may divert to Asia, and vulnerable to weather and shipping delays. They are also logistically constrained due to availability of shipping and regas throughput limitations. This means that during cold snaps or high continental demand, the GB system may struggle to ramp LNG send-out quickly enough to cover both power station and heating loads (which are higher in cold weather)

- Interconnector reversal uncertainty: Continental gas systems are structurally net importers, especially after the closure of the Groningen field in the Netherlands. During European cold spells, they are unlikely to export to GB. Recent investments in IUK /BBL reversibility help, but molecule availability is the limiting factor

- Power-sector rationing: Gas-fired power plants are classified as interruptible customers under the emergency supply hierarchy. If total inflows (UKCS + LNG + Norway + IUK/BBL) cannot meet domestic heating and firm industrial loads, supplies of gas to power generators may be curtailed to preserve household supply (although this is not necessarily rational since most heating systems require power to operate, so supplying gas but not electricity to households would be counterproductive)

In an orderly decline, UKCS production would fall predictably, pipelines would be rationalised, and alternative import capacity scaled up. Although most production forecasts indicate a smooth decline profile over the coming years, this is unlikely in practice because forced decommissioning of offshore pipeline infrastructure would lead to a cliff-edge loss of capacity. This would reduce maximum NTS entry capacity by tens of mcm /day overnight, and shift pressure management southwards changing the utilisation of key compressor stations such as that at Peterborough.

It would also force higher LNG and interconnector reliance without time to build redundancy, or sufficient NTS entry and other pipeline capacity – there are currently constraints that limit the volumes of gas that can be transported from Dragon and South Hook eastwards to consumers in England. Because offshore decommissioning is irreversible, the risk is asymmetric - once a trunkline or compressor is removed, it cannot be reinstated in winter emergency conditions.

Mitigating the risk and impact of pipeline closures

There are several mitigation strategies that could be employed.

The best option would be to remove the fiscal headwinds that are making North Sea gas production uncompetitive, and to allow new drilling to optimise the gas resources owned by the UK. The Government should also consider providing financial support to key pipelines that would support their economics even under lower throughput conditions, essentially removing the economic drivers for decommissioning. This would be analogous to the Capacity Market that ensures lower utilisation of gas power stations due to the use of wind and solar generation does not force their premature closure.

A more expensive, and less viable option would be to develop a gas storage policy. The UK very little gas storage capacity, and while the key facility, Rough, has re-opened, it is not very useful since deliverability rates are far lower than before it closed, and there are few other sites that could be developed for gas storage. Following the closure, Centrica removed the cushion gas and the produced a significant amount of the tail reserves, materially reducing the reservoir pressure and hence the speed with which gas can be extracted.

To make Rough a meaningful source of gas during cold snaps, it would be necessary to either drill new wells and re-inject cushion gas to raise the reservoir pressure – which would require a significant investment – or to install pumps on the production wells. Either option would require new capital expenditure, but the result would not solve the problems caused by a decline in gas from the UKCS.

Finally, Britain could install floating regasification terminals which would increase the amount of LNG GB could accept. Spare NTS entry capacity at Easington and St Fergus would make these the most likely sites, but ship docking facilities as well as storage tanks would need to be built. Depending on the extent of works needed to accommodate large LNG tankers, this is likely to be part of the solution to the eventual decline of the UKCS.

“We think Neso forecasts are too optimistic. We forecast gas production to decline by 70pc by 2030 due to the impact of the windfall tax. That suggests the UK will run out of LNG import capacity as early as 2031, as the current import terminals reach the maximum rate they can deliver gas into the UK grid during winter. The best way to ensure security of gas supply is to maximise domestic gas production,”

- Chris Wheaton, analyst at Stifel

At current decline rates, UKCS inflows to the NTS could fall from around 30 bcm in 2024 to 20 bcm by 2030, with much of the loss concentrated in the north and east coast terminals. This progressively reduces the steady baseload inflow that underpins pressure and linepack flexibility in winter. This will lead to rising import dependence, as GB will rely more on LNG (up to half of peak-day supply) and Norwegian imports (Langeled, Vesterled). From 2028 risks of structural reduction in Norwegian deliveries will also begin to manifest - before then, Norwegian offshore pipeline operator, Gassco, projects stable or slightly higher export capability, although maintenance outages will present some short-term risk.

As UKCS production falls, even if overall gas availability remains adequate on paper, North Sea gas flows will reduce baseload pressure support, increase reliance on LNG logistics, and heighten the risk of generator curtailment on extreme-demand days, beginning as early as winter 2026/27, and increasing year-on-year into the 2030s unless policy change reverses the accelerating decline in UKCS production.

An infrastructure blind spot that represents a serious security of supply risk

Almost all published analysis of GB gas security focuses on the onshore system - the NTS, LNG terminals, storage and interconnectors. Far less attention has been paid to the offshore pipeline infrastructure that delivers gas to the beach in the first place. This is a serious blind spot. Offshore trunklines do not decline smoothly with production, they fail economically once throughput drops below a viability threshold. When that happens, multiple connected fields are stranded simultaneously and entry capacity can fall abruptly.

Because offshore decommissioning is irreversible on winter timescales, this creates a cliff-edge risk to cold-snap gas adequacy that is not captured in current security-of-supply models. Once these pipelines close they will be hard if not impossible to restore, and their closure will push fields that could keep producing into early closure. None of this is captured in the production models.

This Labour Government is not just sleepwalking into disaster by forcing the UKCS into premature decline, it is racing towards it. And for what? Because we’re not reducing gas consumption by reducing North Sea output, we’re simply replacing domestic production with more carbon intensive imports. Irrational ideology is putting our energy security at risk, undermining affordability, increasing real world emissions, and hard-wiring vulnerability into a system that already operates close to its physical limits.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Watt-Logic

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy