The energy transition took centre stage at Investing in African Mining Indaba, Africa’s foremost mining event, putting a spotlight on the US$1.2 trillion opportunity – and the carbon reduction investment dilemma

Robin Griffin, Vice President, Metals and Mining Research

Nick Pickens, Research Director, Global Mining

Wood Mackenzie was privileged to participate in two panel discussions at this year’s Mining Indaba in Cape Town, South Africa. The event positioned Africa – and the supply of critical metals – at the centre of the energy transition.

The unanimous call to action is that an extraordinary investment in new mines is needed, and soon. Most industry participants also agreed on the challenges in doing so. But few in the sector can provide an optimal solution as to who will pay and how the value chain should evolve.

Mine project development isn’t keeping pace with future energy transition demand

Across the many panel discussions and keynote speeches at Mining Indaba, there seemed little disagreement that for energy transition metals – lithium, copper, nickel, cobalt, vanadium and graphite, among others – there is currently a mismatch between future demand and the ability for industry to deliver.

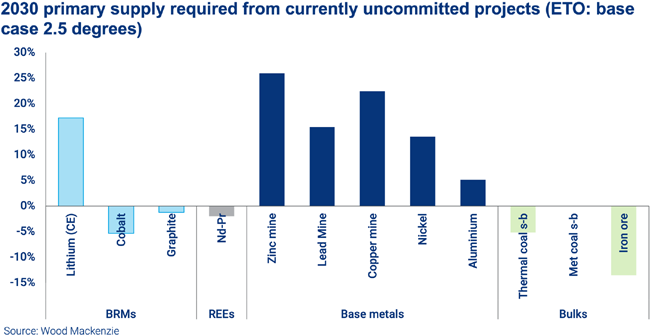

Wood Mackenzie numbers suggest that in order to reach Paris Agreement targets of zero carbon by 2050, copper and aluminium production must double, nickel output needs to rise three-fold and the world will require nine times the amount of lithium produced today.

Overall, an investment of US$1.2 trillion is needed across transition metals supply by 2050. Yet so far project development rates are falling short – why?

The constraints in delivering new mine supply

A major reason is that cash is being returned to shareholders, rather than being re-invested into growth. This keeps investors happy but starves the industry of the necessary investment to meet future energy demand. The risk is a period of rapidly rising metal prices from mid-decade onwards as structural deficits emerge for several key commodities.

A second issue is project lead times. In more mature markets, such as copper, we have seen a lack of investment in exploration, leading to thinning advanced project pipelines and a lack of quality projects.

In less developed ‘green’ metal markets it is also a game of catch-up. It takes 10 to 15 years to prove, develop and ramp up mines for most metals – and this is incompatible with a race to zero carbon in a little over double that time.

The time taken to develop projects is a function of many other factors – heightened country risk, lengthier permitting processes, and a razor-sharp focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles. This all means that meeting investment criteria and gaining a social licence to operate is increasingly difficult.

The investment dilemma

The conflict between the desire to reduce emissions while also hampering the production of metals required to achieve zero carbon is one of the many contradictions exposed along the pathway to zero carbon.

For governments, regulators and communities there is a much stronger emphasis on reducing carbon emissions than developing mines. And the relationship between the two is still not necessarily understood by all. Mining companies themselves are also obliged to invest in carbon abatement. It is required by some regulators, it seems to make sense from an emissions reduction perspective and, when factoring in the impact of carbon taxes, investing capital in carbon abatement rather than new mining projects can also provide better returns.

Ideally, we should be investing in both emission reduction and new mines for vital energy transition metals. And there is this unpalatable reality that if Paris Agreement targets are to be met we probably need to see carbon emissions increase before they can be reduced to zero.

The role of Africa and the implications for supply chains

There is a broad understanding that with around 30% of global mineral wealth, African mining will play a critical role in supplying the materials needed to meet the world’s emissions targets. But there was a united resolve amongst Mining Indaba participants that Africa should be able to meet its own needs and ensure that the benefits of the transition flowed far beyond the mining sector.

There was a pervasive undercurrent of hope. But there was also realism. Change is required to enable the mining sector to reach its potential. A swathe of practical measures is required, from digitised cadastral information to a skilled labour pipeline. But it was energy, logistics and ESG risk that were constant themes.

- Energy reliability and the slow pace of renewable penetration is constraining the move into downstream processing, and restricting the benefits of clean energy to African communities.

- Logistics too must be a priority, whether it’s underperforming rail assets constraining critical mineral supply from South Africa’s northern cape, or weeks-long delays on concentrate supply across the DR Congo/Zambian border. Removing logistics inefficiencies and costs is an obvious prerequisite.

- ESG risks are still the most common refrain. Large and diversified miners in Africa are expanding production but, aside from copper/cobalt in DR Congo, growth rates are slow. Larger mining houses are focusing on decarbonisation at existing sites – a sensible and noble aim, but not conducive to rapidly meeting the supply of critical minerals. Junior miners will be fundamental to Africa’s supply growth.

As we have discussed, many diversified miners – and western investors in general – are hesitant to commit any funds to growth globally, but particularly the African mining sector. There is an acknowledgement of the changes that governments need to undertake, but investors’ requirements need to evolve too. For example, at Mining Indaba there were calls for a change in narrative and approach to investment in artisanal mining in the DRC, to legitimise an informal mining sector that provides around 7% of global cobalt, and upon which an estimated 200,000 jobs rely.

Realising the opportunity in Africa

There is much hard work to do if Africa is to make the most of its enormous mineral wealth. And no shortage of ideas. We heard of innovative financing mechanisms that lower the cost of capital for clean energy projects and mineral exploration. There were also calls for much broader collaboration amongst governments and miners to pool resources, promote technologies and share infrastructure. We also heard requests for investor patience as the changes take place.

Change will not happen overnight – this is an energy transition after all. But the chances of success in achieving zero carbon are greatly increased with stakeholders pulling in the same direction. Alignment on targets among governments, industry and communities will be essential. Regulations need to promote carbon abatement, but also allow the supply of raw materials to achieve it. New pools of investment will also be required, from manufacturers (OEMs), governments and possibly even the oil and gas industry.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Wood Mackenzie

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy