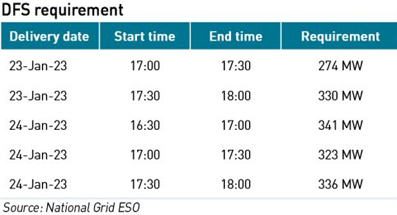

This week National Grid ESO has activated its Demand Flexibility Service (“DFS”) for the first time. The scheme was used for 1 hour on Monday 23 January and 1.5 hours the following day. The coal reserves were also placed on standby each day, although the were not needed. Both DFS auctions attracted 19 participants with bids ranging from £2.80 /kWh to £6.50 /kWh (for some reason there were some bids below the £3 /kWh price floor). Participants are paid as bid above the floor. 659 MW was secured on 23 January and 929 MW on the 24 January.

The bulk of demand for both auctions came from domestic suppliers with Centrica, EDF, EOn, Octopus and Ovo all participating. Octopus alone committed to more than 370 MW of demand reduction in the first auction and 430 MW in the second. 26 participants in total have engaged with the test auctions in which responses exceeded target levels. It will be interesting to see what reductions were actually delivered by consumers once the settled data are available for these two days of active service.

More than one million homes and businesses have participated in tests of the DFS, collectively saving around £2.8 million. In other words, £2.80 each. In my previous blog on this topic, I outlined that people might be able to save up to £7.50 /day but that assumed the service would be activated for 5 hours and that they had not already reduced their energy use. What has emerged is that people taking part in the scheme often were already conscious of energy use and so their reductions were small – some reporting savings of just 30 pence, or they have gone to extreme lengths to cut demand.

There have been stories of families sitting in their cars, or sitting in bed in the dark having turned off every electricity load in the house for an hour. While some may see this as a harmless adventure, there is a real danger that vulnerable consumers may be harming themselves through taking extreme measures to secure savings, not just in terms of heating and lighting, but also turning off fridges and freezers.

There have also been complaints about access to the scheme. In order to participate you need a smart meter, the smart meter needs to be working in smart mode, and your supplier needs to be participating in the scheme. About 1.7 million households have a smart meter that does not function smartly while 14.0 million households have operable smart meters and 13.0 million households have traditional, non-smart electricity meters. There are also reports of people trying to get a smart meter since the DFS was introduced, but being unable to book an engineer, with waiting times of several months with some suppliers. Others see the DFS as a trick to snare people into getting smart meters which they didn’t previously want.

Why were demand reductions needed?

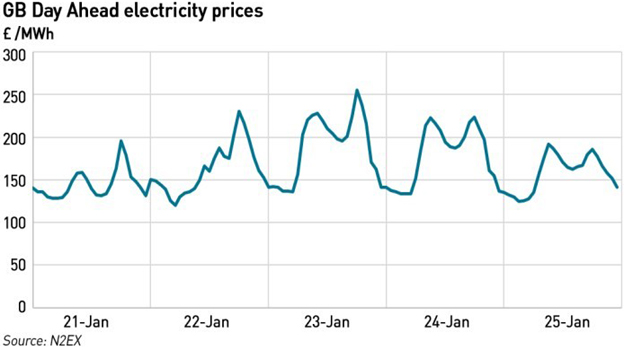

NG ESO determined that low wind output combined with low imports from France during a cold spell was threatening the ability to meet demand. And although imports from France were minimal over the days in question, wind output was higher than it was when two Capacity Market Notices were issued in the previous cold snap in late November. Some have also pointed to market prices which have remained stubbornly un-spiky to suggest that activating the DFS and warming the reserve coal units were little more than a stunt by the system operator.

Day ahead electricity prices on N2EX for this week have been rather un-interesting and prices in the Balancing Mechanism on the 23 January were normal, with high prices in the evening peak on 24 January only reaching £575 /MWh, far below the £1,500 /MWh in late November. If the market was genuinely tight, this should be reflected in prices.

It is also interesting that while ESO instructed the winter coal contingency units to warm on 23rd, 24th and again on the 26th when wind output was much higher, but in each case they were later stood down. Warming these units whether they are used or not has a cost since they have to burn coal in order to be ready to generate. This illustrates one of the inefficiencies of the DFS in that it is exercised at the Day Ahead, so while it might be cheaper to run the coal units instead of the DFS, the DFS cannot be stood down in the same way that the coal contingency can.

In any case, the winter coal contingency is likely to be a one-year phenomenon, so its inefficiencies might not be that important in the scheme of things…the two West Burton units will definitely close permanently in March due to old age, while the Ratcliffe unit has signalled a return to the regular market. That just leaves the two Drax units, but it would be surprising if they were held over in reserve for a year or more. Publicly, Drax is just saying it is committed to a “coal free future” which is ironic considering the emissions both in the supply chain and from the stack from burning wood pellets are much higher than for burning coal, but that’s a whole other story.

The DFS has been an interesting experiment but should not continue in its current form

It’s difficult to understand why the DFS was activated this week. The market appeared to be much better supplied than at other times this winter when the service was not used. It’s tempting to believe that NG ESO decided to use the DFS to prove it could and to set a precedent in what may be the last truly cold spell of the winter. If that was the case, it may come to regret it, since many participants are complaining in the media about the low levels of returns, amid tales of some consumers going to extreme lengths to secure savings. The idea was for people to change the times at which they cooked meals, did laundry or charged electric cars, not to encourage them to sit for hours in the cold and dark.

There have also been reports this winter of fatalities linked to people not heating their homes due to the high cost – most winters there are between six and ten thousand excess deaths that can be attributed to the under-heating of homes, usually causing deaths due to respiratory illnesses, but this was an actual case of hypothermia (body temperature of 35oC or less, compared with a normal temperature of 37oC). Last winter there were 8,500 excess deaths linked with cold homes.

There are many more deaths associated with cold than with heat in the UK: according to a study published in the Lancet, there were 800 excess deaths due to heat and 60,500 deaths due to cold between 2000 and 2019. The NHS recommends that to avoid hypothermia, homes should be heated to at least 18oC and hot drinks/hot meals should be taken daily.

The challenge is to design a demand-response service where:

- Consumers can benefit even if they are already reducing consumption due to high energy costs

- Consumers are not encouraged into self-harm eg by not rewarding reductions below a minimum “healthy” level (which would need some effort to define)

- The benefits are actually worthwhile ie a higher rate per kWh

- The costs of the scheme are lower than alternative sources of winter reserves

Enthusiasts suggest that demand-side response is the future of the energy system, and just about everyone agrees it will have a role to play, but DFS does not seem to provide very much benefit either to the grid or to participants.

Original article l KeyFacts Energy Industry Directory: Watt-Logic

KEYFACT Energy

KEYFACT Energy